Click on a Tab to Read the Article

San Diegan Cliff Dives from 60 to 0

March 29, 2013

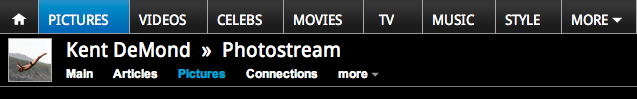

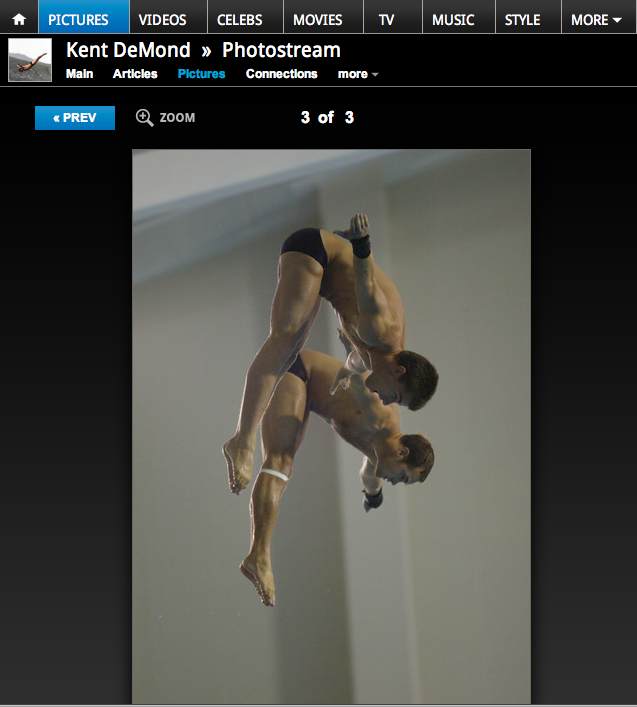

Kent De Mond, Photostream

September 6, 2012

Elite Divers Talk Nerves from a 10-Story High Diving Board. August 24, 2012

Elite divers will be leaping off the top of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) and into the Boston Harbor, doing flips, twists and turns all the way down.

The Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series competition draws crowds by the tens of thousands, and it returns to Boston this weekend.

Starting at 4 p.m. in Boston Saturday afternoon, the diving will begin. It’s free to the public and there will be food, fun, music, and, of course, diving!

The diving board is 10 stories high, 93 feet up in the air, on the roof of the ICA.

Three of the divers participating in the completion are: David Colturi from Michigan, Kent DeMond from San Diego and Steven Lobue from Indiana.

“I guess first and foremost most of us are just pretty fortunate and we feel very lucky that we get to do sort of what we do and that our past training has paid off,” says Lobue.

This could be dangerous.

“There’s all sort of injuries, the main one there is some pulled muscles. I guess worst-case scenario if you have a flat landing, you could get some internal bleeding, and it could be pretty serious.”

Do they ever get nervous up there?

“Yeah, definitely. I mean, everyone one of us are scared and nervous but it’s what we train to do and once you get those first couple dives off at each stop then you kind of relax and you focus and then you kind of just get to enjoy it and really do what you love to do,” Colturi says.

They’ve traveled all over the world, including Portugal and Ireland.

What about the large crowds watching, does that make them nervous?

“I don’t think we get nervous at all really. I get pumped up by the crowd. I think the one thing I get nervous about is just the dive itself and the height. Whenever I see the crowd, it makes me a lot less nervous,” said DeMond.

How do you work your way up to this height?

“The hard thing is when it comes to training, we don’t have a 27 meter platform that we can train on. So most of our dives we do on the 10 meter Olympic level and then the rest is just sort of mental preparation. And then when you get here, you just have to tell yourself it’s the same,” says Lobue.

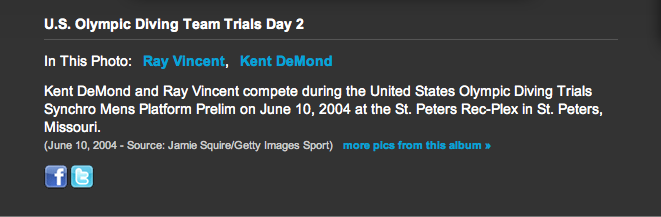

OB Man Helps Put Extreme Cliff Diving On Map. August 2012

Deep Dive at the ICA: Free Falling

August 29, 2012

Cliff-Diving Daredevils Compete in the Azores. July 21, 2012

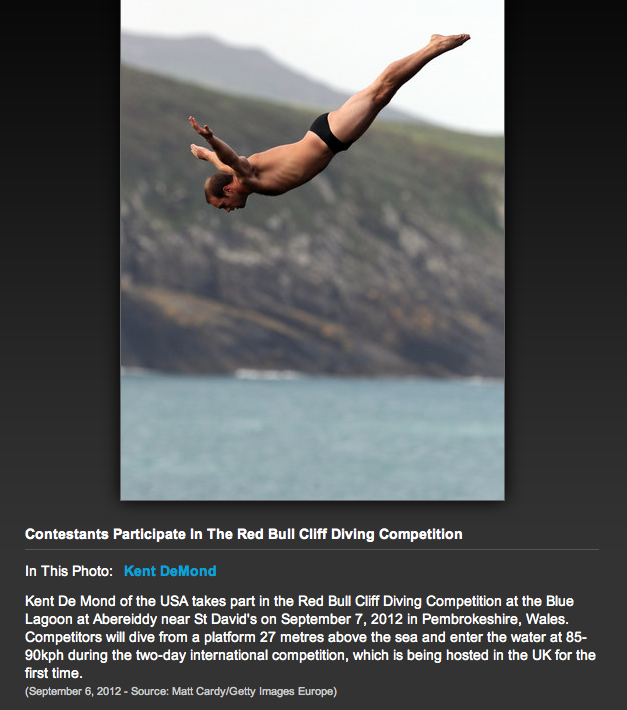

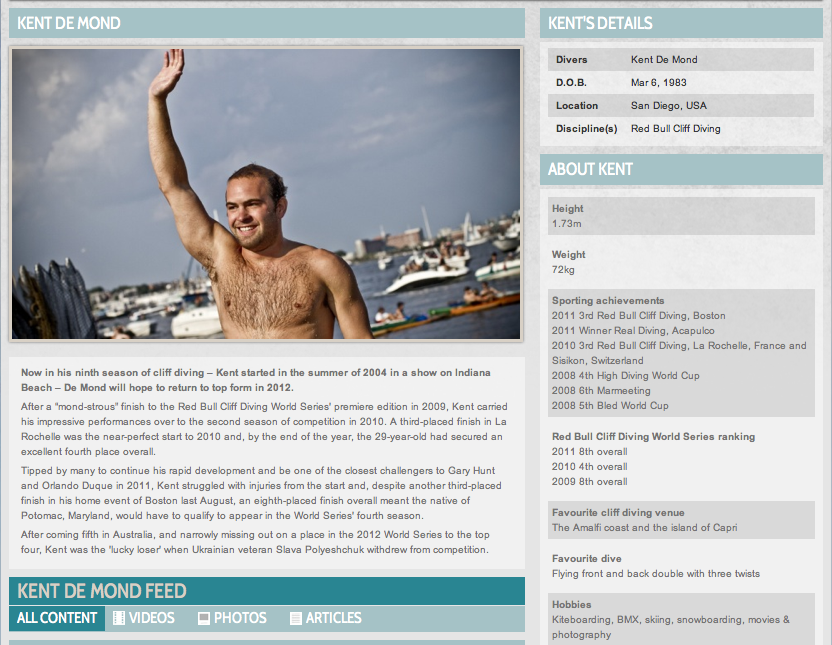

Athlete Profile: Kent De Mond

January, 2012

Cliff Diver Kent De Mond's Career is Taking New Twists and Turns.

September 8, 2011

Cliff Diver Kent De Mond's Career is Taking New Twists and Turns

By Mark Giannotto, Published: September 8, 2011

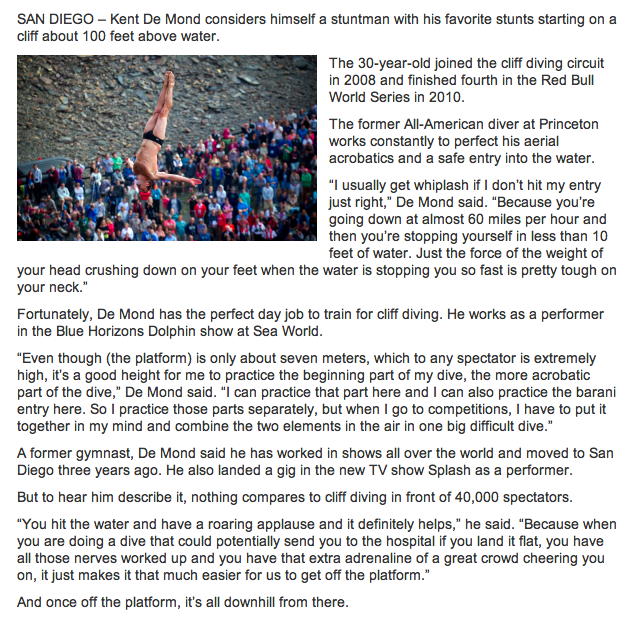

Kent De Mond paces among the pipes and generators on the roof of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. Ninety-two feet below lies his destination — the murky saltwater of Boston Harbor.

The 28-year-old De Mond, who grew up in Potomac, has been jumping from these heights for six years. The settings range from a Mayan sinkhole in the Yucatan to a tiny pool at a summer fair in Richmond.

This is the first professional cliff-diving event held in the continental United States; it’s also the only time the Red Bull Cliff Diving series has come to an urban setting. The winner, who will be seen by 23,000 spectators around the shores of Fan Pier, will earn about $6,200.

Jumping off a building has caused De Mond, one of only two Americans to compete regularly on the world’s top cliff-diving circuit a great deal of consternation. The platform, usually stiff, is shaking like a backyard springboard.

“I think everyone’s pretty scared,” says De Mond, who, like most of his 13 competitors, has a full-time job; his is performing in the dolphin show at Sea World in San Diego.

On a barge down by the shore stand De Mond’s wife and high school sweetheart, Annabelle, as well as his parents and a collection of friends and family that has come to witness him free-fall at speeds exceeding 60 mph.

“I always get butterflies,” Annabelle says, craning her neck skyward as her husband approaches the platform nine stories above.

De Mond walks to the edge, raises his arms and leaps.

It’s just a practice jump. He’s trying to judge the bounce, but something doesn’t feel right. He turns back toward the building and converses with another competitor.

De Mond approaches the edge again. This time, he looks down to give a thumb’s up to the four rescue divers treading water below and the emergency medical personnel standing alert on a nearby boat.

The arms rise again. De Mond’s legs flex. His arms circle below his waist, and he launches.

His body spins violently, rotating through three flips and one-and-a-half twists. Nearing the water’s surface, now upright, he points his toes and tightens his entire body into a straight line. The slightest lean could result in serious injury; a crash landing from 92 feet is equivalent to hitting concrete from 43 feet in the air.

De Mond’s feet smack the water, and his red Speedo disappears into the Harbor. It sounds as if a gunshot has gone off.

“Oh, no,” gasps De Mond’s mother, Joyce. The handheld camera she was filming with drops limply to her side. “Is he okay?”

* * *

The accepted origins of cliff diving date to 1770, when the last independent ruler of Maui, King Kahekili, used a cliff on Kaunolu Bay on the island of Lana’i for an initiation of his local warriors called “lele kawa.” The English translation is “leaping off high cliffs and entering the water feet first without a splash.”

Modern cliff diving got its start in 1934, when 13-year-old Enrique Apac Rios jumped off of La Quebrada in Acapulco, Mexico, which has since become the most recognizable cliff-diving site in the world.

One complication for professional divers today is that they don’t have regular access to cliffs.

“There’s no such thing as a 27-meter platform, so we can never actually practice the whole dive,” De Mond says.

So, three days before an event in which he’ll leap from a castle on the cliffs of Malcesine, Italy, De Mond has driven 90 minutes from his home in San Diego to Mission Viejo, Calif., to train on a 10-meter platform.

As he stretches on gymnastics mats, two young boys approach and ask what he’s doing here. De Mond describes the dives he uses in competition.

“Dude, that’s beast,” one of the boys says.

De Mond starts his training session from a one-meter platform and slowly works his way up the diving tower, focusing mostly on landing correctly. After a dozen dives, he moves to the 10-meter platform, where he starts out with simple maneuvers such as single somersaults.

While practicing a double back flip with one-and-a-half twists, De Mond over-rotates and lands poorly, smacking his entire left arm against the water. When he emerges, his palm is black and blue, with a protruding red welt rising on his forearm.

De Mond shrugs it off. “You gotta do another one when you crash like that.”

He has been dealing with a sprained wrist since March. He injured it completing a rare head-first dive in Acapulco. He won that competition — his first major cliff-diving title — but the injury has affected his performance. After finishing in fourth place overall in 2010, he hasn’t placed higher than seventh in a Red Bull event this year.

In this training session, the wrist has improved enough that De Mond decides to close his workout with a back handstand takeoff that he may use in future competitions.

He bends down at the edge of the platform and slowly raises his legs into the air. His body starts to sway and lean toward from the water. As his lower half drifts above him, De Mond’s arms flex and launch him off the platform.

He’s propelled out instead of up. His somersaults are sloppy, and his twists seem rushed. His body thuds against the water, a large splash in its wake.

But he climbs back up the diving towering, repeating the same routine. Soon, the flips and twists join together seamlessly.

When he finishes for the day, De Mond climbs out of the pool and holds out his arms . They’re shaking.

“Whenever you do a new dive you get the shakes, but you get them afterward when you don’t expect it,” De Mond says with a smile.

* * *

De Mond was drawn to cliffs even as a child.

His mother, Joyce, still sounds scared as she recalls how she would plead with her son to “Come down from there,” when he figured out a way to scale the cliffs outside the family’s beach house in Vancouver, B.C.

She put him in gymnastics class at 5, and when the family moved to the Washington area in 1992, where his father worked for the World Bank and she taught special education, De Mond also picked up summer diving at Seven Locks Swim Club. The flips and twists he learned on the mat became natural on a diving board.

By the time he reached high school, De Mond had dropped gymnastics to dive year-round at the Montgomery Aquatic Center in Rockville as part of the Montgomery Dive Club.

He quickly showed he was talented enough to be part of the Junior Olympic circuit that dominates the weekends of elite youth diving. But he was no prodigy; his two younger sisters, Michelle, 26, and Alexis, 23, both won metro championships at Churchill High School. Kent took second place as a senior. (Both sisters are now professional show divers on cruise ships.)

“He was always second, third, fourth or fifth,” Joyce says.

But off the platform, De Mond’s daring side was beginning to blossom.

He would perform BMX bike tricks in parking lots. Once, he and a couple of friends constructed a homemade half-pipe, and De Mond completed a back flip on his bike, a stunt that his mother found out about when it was pictured in the 2000 Churchill yearbook during his junior year.

One late summer night as a high school lifeguard, De Mond did a standing back flip off the roof of a 10-foot-high pavilion at Seven Locks Swim Club, clearing 11 feet of pavement and landing safely in the pool’s diving well. (I was a lifeguard at Seven Locks that summer and saw it myself.)

It was around this time that De Mond had his earliest encounter with cliff diving. He had worked up the courage to leap off a 10-meter overhang into the Potomac River near Great Falls.

“I saw other people diving off of it, so I just did it,” he explains now. “It felt like a 10-meter platform, but it was just fun to jump off a rock into the river.”

De Mond’s coach at the Montgomery Dive Club, Roland McDonald, says it became clear to him that De Mond was not like his other divers.

“Most divers kind of have that thrill gene a little bit, but Kent displayed an aptitude for aerial awareness, and he seemed to manage to do tricks in the air and never smack,” said McDonald, who coached at George Mason from 1999 to 2010 and is now the head dive coach at San Diego State. “He just kind of figured out how to get out of trouble if he was ever in trouble. That was a good sign.”

When De Mond reached his junior and senior years, his diving began to catch up with his ability to test boundaries. A few college coaches took notice, especially as he seemed so willing to attempt high-difficulty dives. De Mond eventually decided to dive at Princeton, earning all-American status in 2005 and 2006.

But even as De Mond began to reach his potential in traditional diving, McDonald decided it was time to act on the intuition that his pupil had the makings of a high diver. McDonald showed him a few basic skills, such as the Barani flip, a front flip with a half twist that allows a diver to see the water before entry and is used at the end of almost every cliff dive.

The sensation is one that De Mond still remembers.

“You get a rush when you learn something new, and then you just go farther,” he said. “It’s probably the same feeling you get if you play a video game and you get to the next level. The only difference between cliff diving and the video game is that you’re actually gonna get hurt if you don’t do it right.”

* * *

High diving at an amusement park or fair adds elements of danger that are entirely foreign to cliff diving. There are platforms as high as 22 meters and perhaps a handful of springboards varying in height. The pools are never especially wide, and often the water goes only 10 or 12 feet deep.

De Mond spent two summers diving at an amusement park in Indiana Beach, and then another in China, where he finished his senior thesis on art history.

He began traveling professionally, performing for a month or two at a time as part of amusement park shows in South Korea and South Africa, in addition to stops across the United States.

By 2008, De Mond longed for competition again. Australian cliff diver Joey Zuber provided De Mond a list of promoters holding cliff-diving events, and Zuber vouched for him based on a demo video. That connection got De Mond invited to a couple of lower-level cliff-diving events. After he showed promise, Red Bull brought him in as a wild card to an event in Wolfgangsee, Austria. He finished in the bottom half of the competition, but he established his name.

The next year, when Red Bull announced it would expand its cliff-diving event into a series, De Mond received an invitation to join. It was a validation, but De Mond got more pleasure from the experience.

“The thing about doing a cliff dive, as opposed to regular diving, is there’s maybe only a handful of people in the world that can do it,” De Mond says. “But I also think the feeling you get when you do a cliff dive safely — when you just nail the dive — the feeling from being so scared before you do it and the feeling from hitting the water safely and knowing you just did a really good dive, it’s the best feeling.”

* * *

De Mond takes Interstate 8 East from his one-bedroom apartment to Sea World every morning, the theme park’s revolving 320-foot-high Sky Tower looming in the distance.

He is almost always the only commuter riding his bike.

“The more dangerous way is faster,” he says. “I just hug the railing.”

This is the busiest time of the year at Sea World, and De Mond and the rest of the cast of the “Blue Horizons” dolphin show are preparing for another five-show day. De Mond and 12 divers and aerialists meet in a small building backstage that’s part break room, part storage shed. Here, De Mond and company change into costume and apply the rainbow makeup that’s supposed to reflect their roles as tropical birds.

During each morning show, nearly 3,000 spectators fill Dolphin Stadium. The first seven minutes focus on the dolphins and their trainers. But as two dolphins glide along the glass of the performance tank, splashing the front rows of the crowd with their fins, De Mond and three other divers emerge. Dressed in brightly colored tights, De Mond conspicuously climbs a ladder built on the back portion of a 7.5-meter structure that sits to the left of the audience.

Once he is on top, the narration of the show points the audience toward De Mond as the dolphins swim backstage. De Mond puffs out his chest and looks toward the sky, a superhero perched like a bird on a tree limb. “A little character acting,” he’ll later joke.

He turns his back to the audience and launches himself into the water. In a flash, he has completed one-and-a-half back flips with one-and-a-half twists and drawn “oooohs” and “aaaahs” from the crowd.

Ten seconds later, De Mond is back on top of his 7.5-meter platform, preparing to use a small trampoline for his next dive. With the extra height, he completes two-and-a-half front flips with a full twist, his body contorting so quickly, and so much, that he barely has time to come out of his tuck and land headfirst.

Still, the dolphins are the stars here. After De Mond’s second dive, he poses for the crowd once more and heads backstage, then reemerges to wave a giant flag at end of the show.

“It can get monotonous,” De Mond says.

But “Blue Horizons” is a steady gig with a consistent paycheck. De Mond makes from $150 to $255 a day, depending on how many shows he does.

“I think most of us have traveled around the world, but just throwing your clothes in a suitcase, it gets kind of old,” diver Selena Laniel says.

De Mond chimes in. “And then if you have a month where you’re not doing any shows, you start to run out of money.”

* * *

It’s an unusually humid August day, and more than 100 boats and kayaks ring the landing zone within Boston Harbor. Inside an auditorium at the Institute of Contemporary Art, divers warm up on stationary bikes or with walking handstands. Another simply juggles three balls.

De Mond is in third place after earning scores of 8 and 8.5 on a reverse flip the day before.

On this afternoon, he’ll perform at least two more dives. If he’s among the top six afterward, De Mond will advance to the finals — a feat he hasn’t accomplished this season.

On this afternoon, he’ll perform at least two more dives. If he’s among the top six afterward, De Mond will advance to the finals — a feat he hasn’t accomplished this season.

Before he climbs the seven flights that lead to the roof, Annabelle kisses him and says, “I love you.” It’s the couple’s one-year wedding anniversary today.

As the announcer introduces him to the crowd, De Mond walks to the edge of the platform. He raises both arms into the air and waves to the masses. Down on the barge below, all of his family and friends are cheering loudly in matching bright yellow T-shirts that read “Demondster,” his nickname on tour.

The crowd quiets. De Mond launches himself into the air, his arms out wide and his chest aimed directly at the water, as if he’s going to perform a 92-foot swan dive. In a flash, his body somersaults once, and he controls his trajectory so he lands straight up and down.

The water bubbles as he breaks the surface. The splash is minimal.

De Mond emerges with a huge smile. The judges agree, and he earns 9’s and 9.5’s. Entering the next round, he’s still in third place.

“That’s exactly what I was looking for,” he says, making his way back up the building. “But this one coming up is the important round.”

His next dive is a triple front flip with one-and-a-half twists, the same one that went so poorly during practice. It doesn’t help that, two divers before, Luxembourg’s Alain Kohl performed the same dive and earned 8’s and 8.5’s.

But De Mond strides to the edge of the platform with a confident gait. He raises his arms and doesn’t wait long to leap.

He whirls his body through the air, and when he enters the water, the splash is again small. The whooshing sound is like a bag being vacuum-sealed, a telltale sign that De Mond has “ripped” the landing.

When De Mond’s head pops out of the water, he pumps his fist in celebration, even before the judges’ scores confirm he has performed better than Kohl.

As De Mond climbs the ladder to the barge, he finds Annabelle and hugs her. His score puts him in second place, and with just three divers remaining, he’s guaranteed a spot in the finals.

De Mond’s final dive is the most difficult. His back is to the water this time. He arches his toes upward on the edge, one small slip or wind gust away from falling off the platform.

But “the nerves were gone,” De Mond would say later.

He propels off the platform, completing three back flips and two full twists. The splash isn’t huge, but it’s his lowest-scoring dive of the day.

Nonetheless, De Mond is all smiles when he returns to the barge. He hugs his family and puts his arm around Annabelle’s shoulder as the final two divers complete their dives.

After fellow American Steven LoBue receives a major score reduction on his final dive, De Mond takes third place — back on the podium of a Red Bull event for the first time in more than a year.

He is presented a 20-pound bronze trophy, and pops open a bottle of champagne. He sprays it all over the winner, Great Britain’s Gary Hunt, then takes a long swig.

Another cliff conquered.

“Sometimes you step on the platform, and you have all this stress built up,” De Mond says. “But I was just in the zone. I was having fun. That’s basically the reason why I started high diving.”

Mark Giannotto covers Virginia Tech for The Post’s sports section. He can be reached at giannottom@washpost.com.

http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2011-09-08/lifestyle/35274012_1_cliff-la-quebrada-kent-de-mond

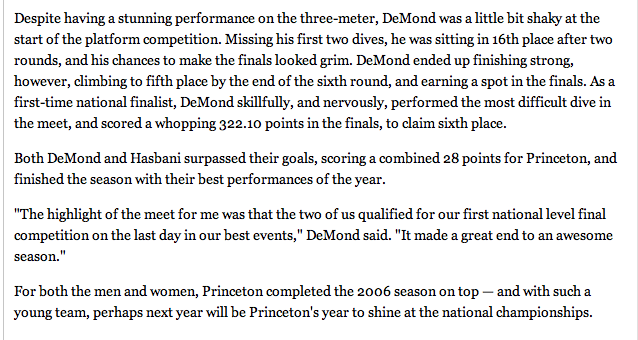

Photo shoot for Vanity Fair Italy

July 27, 2011

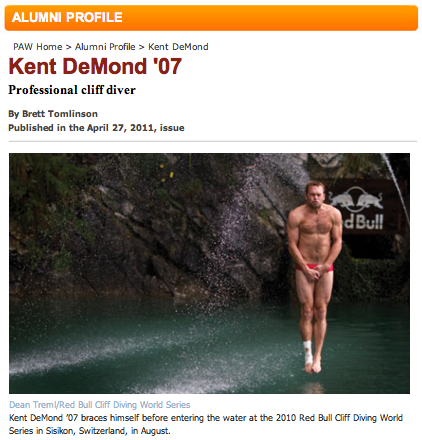

Alumni Profile: Kent De Mond, Professional Cliff Diver. April 27, 2011

Former Tiger All-America Kent DeMond Wins Major Cliff Diving Competition. March 10, 2011

Diving In: Diving Photos Around the World. September 3, 2010

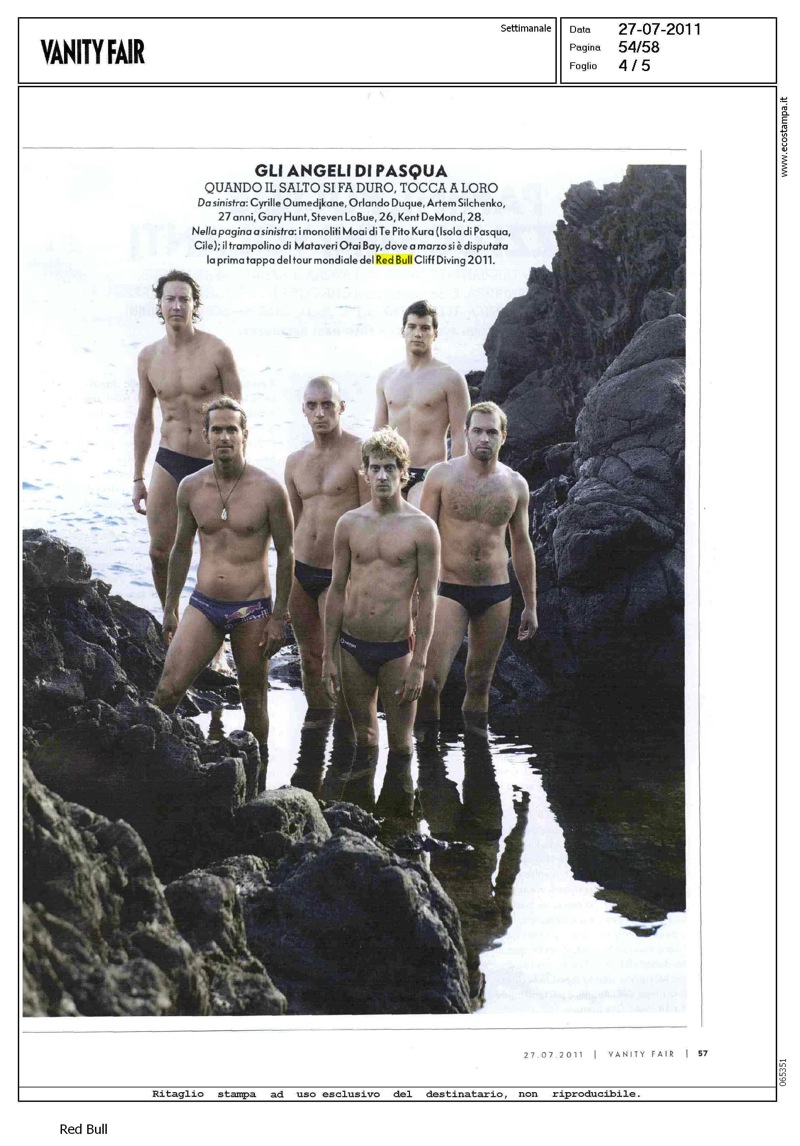

X-treme inspiration on the first day of the cliff diving tournament in La Quebrada. November 23, 2008

Hasbani and DeMond are All - Americans. March 28, 2006